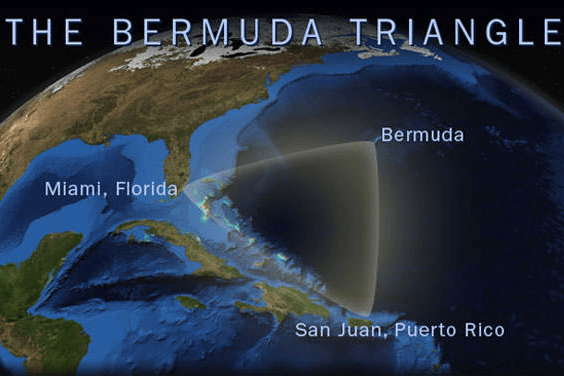

The sea has always demanded stories. From sailors’ songs to modern black box recordings, we try to pin down the unknowable in a place that doesn’t give up its secrets easily. And nowhere is that truer than in the rough wedge of ocean bordered by Miami, Bermuda, and San Juan, Puerto Rico—a place we’ve come to call the Bermuda Triangle.

Some scoff at the name. Others won’t sail through it without a blessing. But for over a century, this patch of ocean has pulled vessels and crews beneath the waves, leaving no wreckage, no messages, and no chance to say goodbye.

Two of the Triangle’s most enduring and chilling cases are the USS Cyclops, lost in 1918, and Flight 19, a routine Navy training mission that vanished in 1945. Decades apart, both incidents share a common thread: highly experienced crews, good weather, and complete, unresolved disappearance.

They didn’t go down quietly. They simply never came back.

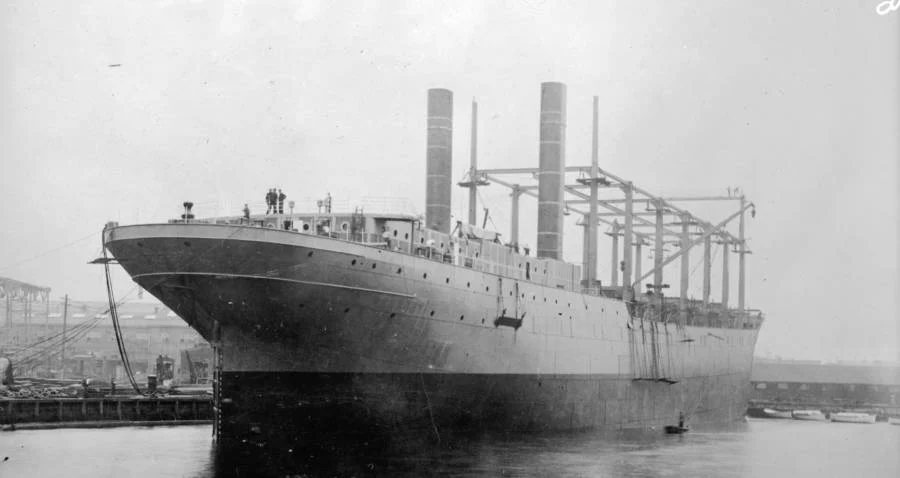

The USS Cyclops: 306 Souls Lost

It was March 4, 1918, in the final year of World War I. The USS Cyclops, a massive U.S. Navy collier ship, left the port of Barbados en route to Baltimore, Maryland. She was carrying over 10,000 tons of manganese ore, a vital component for wartime steel production. Onboard were 306 people, including sailors, civilians, and crew.

She never arrived.

No SOS. No distress call. No floating debris. No oil slicks. In the days and weeks that followed, the U.S. Navy launched one of the largest search efforts in its history, covering hundreds of miles. They turned up nothing.

President Woodrow Wilson himself remarked on the baffling nature of the loss:

“Only God and the sea know what happened to the great ship.”

And for over 100 years, that’s where the case has remained—filed under mystery.

A Trusted Vessel

The Cyclops wasn’t a fragile or inexperienced ship. She was launched in 1910 and had already served with distinction during the Veracruz Expedition in 1914. Stretching over 540 feet, she was one of the largest Navy cargo ships at the time.

But in the months leading up to her disappearance, things had begun to go strange.

Commanding the Cyclops on her final voyage was Lieutenant Commander George W. Worley, a German-born officer with a reputation for strictness—and for erratic behavior. Some crewmembers reportedly found him unstable. In fact, rumors later surfaced that he’d clashed with other officers during the journey and may have been acting erratically in Barbados.

A confidential letter sent to Navy command—declassified years later—hinted that morale aboard Cyclops was “deeply compromised.”

Then came the cargo.

The manganese ore she carried was dense and heavy, and the Cyclops was reported to be riding low in the water when she left Barbados. Some engineers have since speculated that the ore might have shifted mid-voyage, compromising her balance.

But there were no rough seas reported. Weather was mild. Communications were fully operational. There was nothing—no clue—to suggest what might have brought her down, if she sank at all.

No Wreckage. Ever.

More than a century later, no part of the Cyclops has ever been found. Not a lifeboat. Not a hull fragment. Not a body. Several sonar missions and deep-sea searches have been mounted, especially after the rise of deep-sea submersible technology, but nothing has ever turned up.

And that’s not the only twist.

Two of her sister ships, the USS Proteus and USS Nereus, both converted to cargo duty during WWII, vanished under nearly identical circumstances in the same region—without distress calls, without debris, and without warning.

Whatever took Cyclops, it seems, may have come back for more.

Flight 19: The Training Run That Disappeared

If the Cyclops case is disturbing for its silence, the Flight 19 incident is unnerving because it unfolded, step by step, in real time—recorded through radio transmissions until everything suddenly went dead.

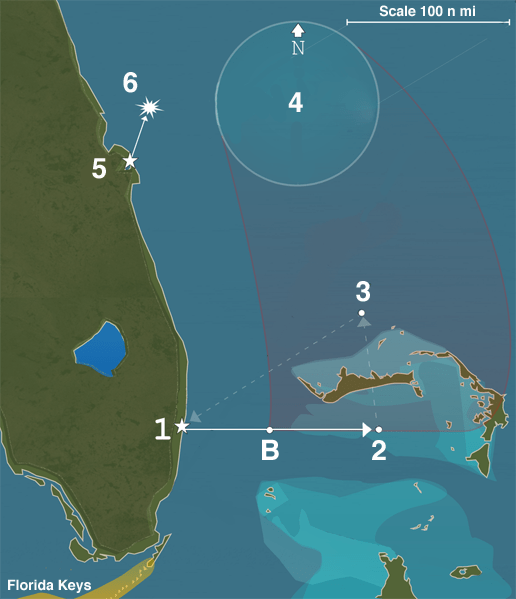

On December 5, 1945, five U.S. Navy TBM Avenger torpedo bombers took off from Fort Lauderdale Naval Air Station at 2:10 p.m. for what should have been a routine three-hour training flight. They were led by Lieutenant Charles C. Taylor, a decorated pilot with over 2,500 flying hours.

The mission was called Navigation Problem No. 1. The plan was to fly east over the ocean, turn north, then return to base. But shortly after the second leg of the flight, things began to go wrong.

“We Can’t Tell Where We Are“

At 3:40 p.m., Fort Lauderdale tower received a transmission from Taylor:

“We can’t find west. Everything is wrong. We can’t be sure of any direction. Everything looks strange, even the ocean.”

Control attempted to direct Taylor back to base, but his responses became increasingly confused.

“We’re not sure where we are. We think we must be about 225 miles northeast of base…”

Later transmissions from other pilots in the group confirmed worsening weather and failing compasses. Some of them wanted to change course, but Taylor hesitated. He thought they were over the Florida Keys, meaning they’d flown too far south and needed to head northeast. In reality, they were already far northeast, and turning further out to sea was the worst possible move.

At around 6:20 p.m., the last radio transmission came in:

“All planes close up tight… We’ll have to ditch unless landfall… when the first plane drops below 10 gallons, we all go down together.”

Then silence.

Search and Rescue: More Questions Than Answers

That night, a Mariner rescue plane with 13 crew members was dispatched to find Flight 19. Less than 20 minutes after takeoff, it also vanished. A tanker off the coast later reported seeing a fireball in the sky—a possible mid-air explosion—but no wreckage was ever recovered.

In total, 27 men were lost. No wreckage from Flight 19 was found during the search. Some debris believed to be from the planes has washed up over the years, but none of it could be definitively linked.

The official Navy report originally blamed Taylor, citing pilot error. But after a review, the final verdict was changed to:

“Cause: Unknown.”

Common Threads and Lingering Theories

So what happened to the USS Cyclops and Flight 19?

Theories abound.

Some are grounded in science. Sudden squalls, underwater methane gas eruptions, magnetic anomalies, and rogue waves have all been proposed. In the case of Flight 19, navigational confusion and compasses affected by solar storms or magnetic variation have merit.

Others wander into the paranormal. Alien abduction theories gained traction in the 1960s and ’70s, especially after the Bermuda Triangle was popularized by authors like Charles Berlitz. Some claim that the region contains a portal—or even an underwater base. These claims are impossible to verify, but they’ve never fully gone away.

In the Cyclops case, there’s also the shadow of sabotage. With the U.S. deeply involved in WWI and Worley’s questionable background, espionage and deliberate scuttling have been suggested, though no evidence was ever found.

Then there’s the matter of repetition. Cyclops, Proteus, and Nereus—all collier ships—vanished under similar conditions in the same zone. Flight 19 and the rescue plane vanished in sequence. Coincidence? Or pattern?

Skeptics and the Statistical Reality

Skeptics argue that the Bermuda Triangle is more folklore than fact. The U.S. Coast Guard does not recognize the Triangle as a danger zone, and analysis shows that the number of disappearances in the area is statistically on par with other heavily traveled ocean regions.

But that logic doesn’t explain the Cyclops.

It doesn’t explain Flight 19—radioed, tracked, and then gone.

And it certainly doesn’t explain how, with modern sonar and submersibles, we still haven’t located a single piece of either.

The Sea Keeps Its Secrets

People often ask if the Bermuda Triangle is real. The answer depends on what you mean.

Is it cursed? Maybe not. Is it dangerous? No more than other seas.

But is it a place where, sometimes, things go quiet—too quiet—and never return?

Yes. That much is true.

And that’s the kind of mystery that doesn’t get solved with numbers or sonar. It’s a question that pulls at something older. Something harder to name.

As for the USS Cyclops and Flight 19, their stories remain unfinished. The logs stop mid-sentence. The ocean closes in. And all we can do is listen—to what’s missing.

Discover more from Midnight Ghostlights

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.